In the late 1950s, a bold artistic vision was born through a commission that would become one of the most iconic, complex, and emotionally charged series of artworks in American modern art: the Seagram Murals by Mark Rothko. These paintings, intended for the opulent Four Seasons Restaurant in the Seagram Building in New York City, represent a pivotal moment in Rothko’s career. More than just abstract shapes and rich color fields, the Seagram Murals reflect his deep philosophical beliefs, psychological intensity, and a stark critique of materialism and elitism. The project ultimately culminated in a dramatic refusal by Rothko to allow his work to hang in a setting he found ideologically incompatible with his intent.

Commission and Concept

The Seagram Building and the Four Seasons Restaurant

In 1958, Mark Rothko was approached to create a series of large-scale paintings for the Four Seasons Restaurant, housed in the newly constructed Seagram Building on Park Avenue in Manhattan. The building, designed by renowned architects Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Philip Johnson, was a symbol of modern luxury, corporate success, and architectural refinement. The Four Seasons was expected to become one of the most fashionable dining establishments in New York City, frequented by high society and business elites.

Rothko was offered an unusually generous commission reportedly the highest ever given to a living artist at that time. However, Rothko did not see this as a mere commercial opportunity. Rather, he viewed the project as a chance to challenge and confront viewers within a luxurious, high-status context. His goal was not to beautify a space, but to instill a somber, almost oppressive atmosphere through his use of color, scale, and emotional intensity.

Artistic Philosophy and Intent

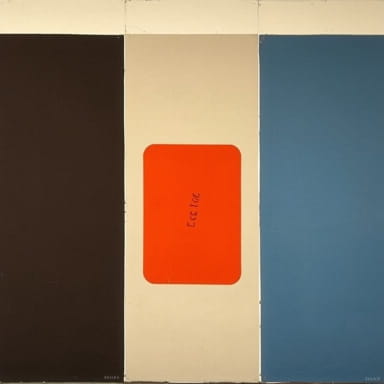

Rothko’s approach to painting had evolved significantly by the 1950s. Moving away from figurative work, he embraced abstract expressionism, especially color field painting. His compositions often consisted of soft-edged rectangular forms stacked vertically, with intense but carefully modulated color fields. But behind the aesthetic simplicity was a deep spiritual and emotional resonance. Rothko sought to provoke feelings of awe, dread, transcendence, and introspection. He likened his paintings to religious experiences, often referencing mythology, tragedy, and the sublime.

For the Seagram Murals, Rothko envisioned a cohesive, immersive environment. The dark reds, maroons, and blacks of these paintings formed a stark contrast to the usual brightness of his earlier works. These were not meant to comfort; they were designed to confront to make diners feel as though they were trapped in a space that evoked a temple or tomb. His use of dark, saturated colors created a claustrophobic atmosphere, and the scale of the canvases further overwhelmed the viewer.

Creation of the Seagram Murals

Working Process

Rothko worked on the Seagram Murals in a studio in his East 69th Street home, which he had adapted to accommodate their large scale. Over the course of the project, he painted around 30 canvases, experimenting with different configurations and shades. Although not all were intended to be installed, each work was part of a broader conceptual whole.

The color palette was deliberately moody and somber, dominated by crimson, plum, ochre, and charcoal. Unlike many of his earlier paintings, these works had more clearly defined structures, with vertical columns and portals giving the sense of architectural formality. These visual motifs echoed ancient structures and created a contemplative, even funereal ambiance.

Spiritual and Psychological Undertones

Rothko was influenced by Nietzsche’s philosophy, especially the idea of the Apollonian versus Dionysian duality. The Seagram Murals reflect this conflict order versus chaos, serenity versus despair. The dark, heavy tones evoke mortality and isolation, making the works unsuitable for the celebratory, elite atmosphere of the Four Seasons. Rothko wanted people to feel engulfed by the paintings not simply entertained by them.

Rejection of the Commission

The Turning Point

Despite his initial enthusiasm, Rothko began to grow uneasy about the context in which his paintings would be displayed. In 1959, after visiting the restaurant and observing its clientele, he realized that the setting would trivialize his vision. The idea of wealthy patrons enjoying lavish meals surrounded by paintings that were meant to evoke existential dread disturbed him deeply.

Rothko famously said he hoped to ruin the appetite of every son of a bitch who ever eats in that room. This statement captures his disdain for the superficial glamour of the restaurant and his desire for art to be profound, not decorative. Ultimately, he returned the payment and withdrew from the project. None of the murals were ever installed at the Seagram Building.

Aftermath and Legacy

The decision to reject the commission was an act of integrity and rebellion. It reinforced Rothko’s commitment to authenticity in art and his resistance to commercialization. Though the murals were not shown as originally intended, their importance only grew with time. They became a defining part of Rothko’s legacy and are now considered among his most powerful works.

The Murals Today

Tate Modern and Beyond

Today, several of the Seagram Murals are housed in the Tate Modern in London, in a specially designed Rothko Room that aims to preserve the immersive experience the artist intended. Other pieces from the series can be found in the Kawamura Memorial DIC Museum of Art in Japan and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

The Tate’s installation follows Rothko’s wishes as closely as possible, with dim lighting, quiet surroundings, and a space that allows viewers to fully engage with the emotional weight of the work. The murals continue to evoke intense reactions, drawing in audiences who seek meaning beyond aesthetics.

Impact on Contemporary Art

Influence on Installation Art

Rothko’s work on the Seagram Murals is considered a precursor to modern installation art. His vision of an enveloping environment where the artwork dominates the physical space inspired later artists to think of exhibitions as holistic experiences. The idea that a painting could interact with the architecture around it opened up new possibilities for contemporary art.

Rothko’s Enduring Message

The Seagram Murals remain a profound statement about the purpose of art in society. Rothko’s refusal to compromise his ideals challenged the notion that art should conform to market demands or social settings. His insistence on emotional depth and spiritual engagement speaks directly to viewers even today.

These works serve as a reminder that art can be more than visual pleasure it can be a confrontation with the self, with mortality, and with the values we hold. In a world increasingly shaped by consumerism and spectacle, the Seagram Murals stand as a testament to art’s power to resist, to provoke, and to elevate.